As State Opera South Australia embarks on its forthcoming production of The Marriage of Figaro, we take a look at the evolution of the story and the themes within it. From its origin as part of The Figaro Trilogy by Beaumarchais, the operatic adaption of The Marriage of Figaro by Mozart is now one of the world’s top 10 most performed operas. Yet it has undertones of rebellion and speaks of social themes and injustices as much today as it did over 200 years ago.

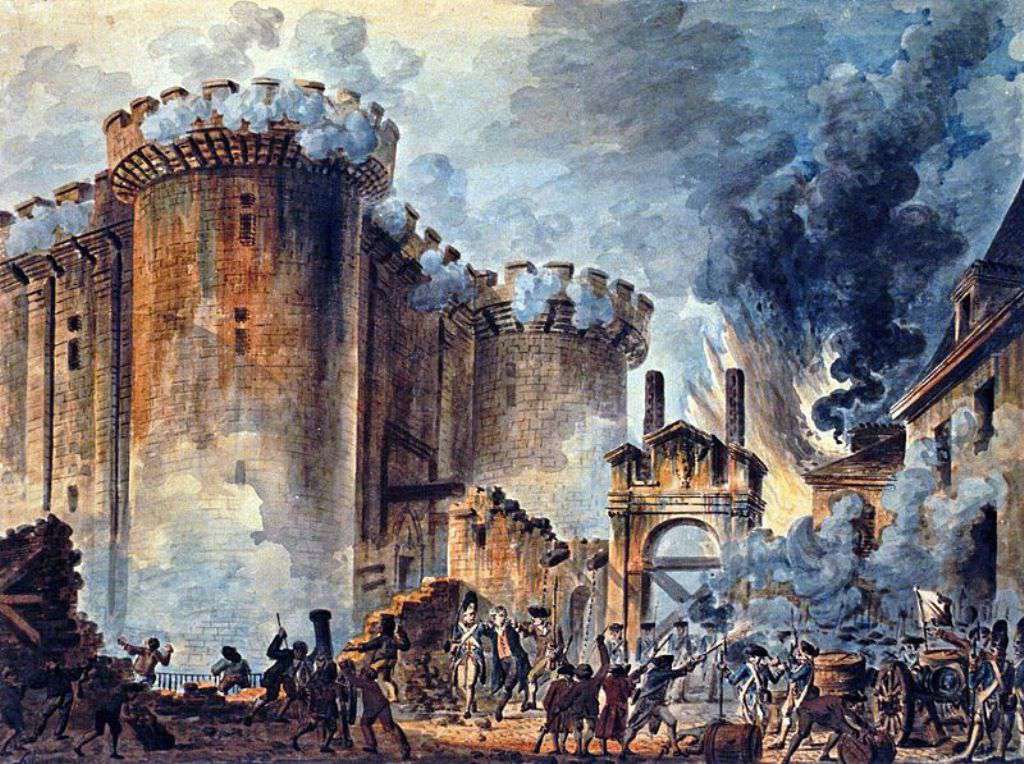

Beaumarchais and the French Revolution

Pierre Augustin de Beaumarchais wrote his plays in The Figaro Trilogy between 1775-1791. Comprising of The Barber of Seville (1775), The Marriage of Figaro (1778), and The Guilty Mother (1791), the trilogy is synonymous with themes of class inequality and social rebellion and drew on the political power and social imbalance rife at the time.

Although Beaumarchais became part of King Louis XV’s court, he had humble beginnings. The son of a master watchmaker, he was apprenticed to another master to learn the trade. He proved talented and invented a new mechanism to make pocket watches more reliable. His boss, however, took the credit for the invention. His father simply advised “c’est comme ça” (“that’s how it is”) in reference to lower classes being overlooked and used by the upper classes. This injustice did not sit well with Beaumarchais and prompted him to rebel through his writing.

The trilogy strongly hints at Beaumarchais’ interest in the political perversion of the upper classes and the social power of the lower classes. Beaumarchais, crafty and cunning, even uses his central character, Figaro, as a slight towards the aristocracy. In the first play, The Barber of Seville, Figaro is the title character, the barber, and one theory suggests that the character was named and employed as such thanks to a derivation from an 18th century French idiom. ‘Faire la barbe’ or ‘faire la figue’ is meant to taunt someone or show disdain via a gesture the equivalent of today’s ‘flipping the bird’. This paints Figaro as someone who, like the young Beaumarchais himself, shows a rebellious streak towards the aristocracy.

The play was well received by the public for whom it was written. Beaumarchais’ use of comedia dell’arte to put across messages was highly effective, uniting audiences through laughter whilst portraying serious political messages. However, Louis XV was angered by the play’s implications, recognising dissent and disrespect towards the nobility, and banned its performance.

The play found other audiences and continued at Thêâtre Français, Theatre Royal, and Covent Garden. It continued to spread and be well received, however its message was a foreshadowing of what was to come: the French Revolution.

Mozart and the opera

The play had caused a sensation. Written at a time of growing civil unrest, the subject matter of servants rising up and outwitting their masters outraged the aristocracy. This led to it being banned in many cities, including Vienna where Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was based at the court of Emperor Joseph II.

The emperor’s sister, the ill-fated Queen Marie Antoinette, kept Joseph informed of the social unrest in France which was fueled in part by Beaumarchais’ writing. So, in order to obtain permission from the emperor to use such a controversial subject for a new opera, Mozart’s librettist, Lorenzo Da Ponte, stripped the play of its most provocative messaging.

In the play, Figaro’s Act V monologue directly confronts the nobility and their failings. In Mozart’s opera, these political outcries are disguised by changing the script to address gender rather than class conflict. The themes and truth of social discrimination were disguised through the lens of gender inequality but were still craftily demonstrated.

With their plans approved, Mozart set to work and completed the music in just six weeks. Da Ponte struggled to keep up with him.

Themes of inequality in modern productions

Even though The Marriage of Figaro story is over 200 years old, the topics of social and gender inequality are still prolific injustices today. The themes presented and interwoven by Beaumarchais, Mozart and Da Ponte in their works have as much relevance in modern productions of the opera as they did in mid-18th century Europe.

Connecting the work to the modern day, the equivalent of Beaumarchais’ courts full of Kings, Emperors and nobles can be seen in today’s upper classes with world leaders and political figures such as Donald Trump, Bill Clinton and Barnaby Joyce conjured from current affairs and the news.

Brought to the fore in Mozart’s adaptation, one particularly thought-provoking example is gender inequality. This is played out between the Count and Susanna, his subordinate and Figaro’s betrothed. The opera sees the Count exercise his ‘droit de seigneur’, the feudal right to bed his servants on their wedding day. Not necessarily a common occurrence today but a concept which can, unfortunately, be easily recognised with echoes of the #MeToo movement, the rape case of Brittany Higgins in Australia, and the overthrowing of abortion laws in Roe vs Wade in the USA. For the longest time, women have been subjected to politicians perverting the course of justice, becoming victims of their ability to wield great power.

The Marriage of Figaro is a comedy, yet there are tones in modern productions harking back to the dissonance of Beaumarchais’ original work. The pluckiness of the author writing his play, full of cheek and defiance, is reflected in the lower social-class characters of Figaro and Susanna, and the Count is depicted as somewhat of a fool, yet a powerful fool who can have real impact on those around him. Just as class imbalance did back in the days of the French Revolution.

Although Beaumarchais’ play was banned for being too political, both young and old can recognise elements in State Opera’s modern interpretation which will speak to them on different levels. Whether it is characters or locations, themes or concepts, there is something that can be easily recognised and understood while enjoying one of the world’s greatest operas.